'How good could I have been?' 50 years since LeFlore made MLB debut with Tigers

Billy Martin's enthusiasm for giving underdogs a shot led to one of baseball's most amazing rags-to-riches stories.

No matter what you think of Billy Martin, one thing is certain. He was a beacon of hope for the underdog.

He did it twice as manager of the Tigers.

John Hiller, the lefty Swiss army knife of a pitcher, was in his kitchen on a January morning in 1971, having coffee and smoking a cigarette.

Then, his life changed.

Pain up and down his arm and chest. Cold sweat. Something was very wrong.

Hiller, at age 27, was having a heart attack.

He missed the ‘71 season, Billy’s first as Tigers manager. Team management was ready to close the book on Hiller’s pitching career, offering him a job as a roving instructor.

But John Hiller wasn’t ready to quit.

He implored Billy Martin for another chance on the mound. Martin convinced GM Jim Campbell to let Hiller give it another try. In 1972, Hiller returned to the Tigers on July 8, throwing three innings in Chicago. He appeared in 24 games in ‘72. The next year, Hiller saved 38 games and was the AL Fireman of the Year. He ended up pitching for the Tigers past his 37th birthday.

We’re coming up on the 50th anniversary of the fruits of Billy Martin’s second reclamation project with the Tigers.

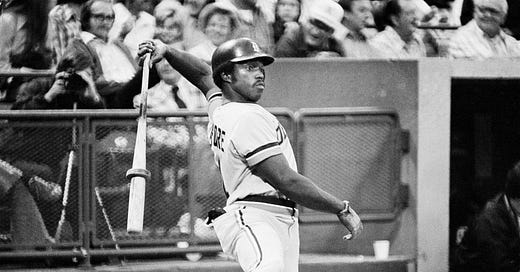

On August 1, 1974, Ronnie LeFlore made his big league debut with the Tigers.

He literally wouldn’t have done so without Billy Martin’s support.

Martin was no longer the manager of the Tigers in ‘74, but he paved the way for the troubled LeFlore to ascend from the prison yard of Jackson State Pen to a big league diamond.

The story of LeFlore is hardly a newly-told one but I’ll be darned if it hasn’t been 50 years!

The Lindell AC was an iconic watering hole in Detroit, located on Cass Avenue near Michigan Avenue, about a mile or so from Tiger Stadium. There are sports bars and then there is the Lindell. I feel sorry for those who never got a chance to be a patron.

The Lindell was owned by the Butsicaris brothers—Jimmy and Johnny. Billy Martin was a frequent visitor—as a player, manager of the Twins and of course as skipper of the Tigers. As such, he struck up a friendship with the brothers Butsicaris.

LeFlore, meanwhile (year of birth is officially 1948 but that has long been questioned as making Ronnie 2-3 years too young), wielded a rifle in an armed robbery of a Detroit liquor store in January 1970. He was convicted and sentenced to 5-15 years in state prison.

LeFlore never played organized sports as a kid or as a teen. In fact, his first experience at playing baseball came on the prison yard at Jackson.

A fellow inmate named Jimmy Karalla, in the pen for extortion, was so impressed by LeFlore’s raw baseball acumen that he reached out to his good friend, Jimmy Butsicaris. Karalla knew that Jimmy B was tight with Tigers manager Martin.

Would Billy Martin visit Jackson State prison to watch LeFlore play baseball?

Of course he would!

Billy’s sojourn to Jackson in May 1973 didn’t come without resistance from the conservative, button-downed Tigers organization.

Billy Martin wasn’t impressed by the push back from Campbell and owner John Fetzer.

“Where do you think you got Gates Brown? Kindergarten?” Billy told Campbell, referencing the legendary Tigers pinch-hitter extraordinaire, whose youth was pocked by brushes with the law.

Good point.

So Billy watched LeFlore play in prison, was duly impressed and he pulled some strings to get Ronnie a one-day pass out of the clink so he could have a tryout at Tiger Stadium.

LeFlore worked out in front of Tigers players and management and while his skills as an outfielder were rough, his bat was professional quality. But it was his speed that caused eyes to blink.

The Tigers, for decades prior to LeFlore, were typically a team filled with power but not speed. They didn’t steal a lot of bases whatsoever, as a rule. So here comes LeFlore, who was fast. And Billy Martin loved to manufacture runs. He just didn’t have a roster that could do that.

As a condition of Ronnie’s potential parole, the Tigers signed him. He was paid a $5,000 bonus and $500 per month for the rest of the 1973 season. He was assigned to Class A Clinton, where his manager was a 29-year-old failed player named Jim Leyland.

“When I was told I was going to get him, frankly, I didn’t know what to expect,” Leyland recalled. “I presumed you could have all sorts of problems with a kid on parole. Could he cross state lines with the ball club? Did I have to keep him out of bars and pool halls? What happened if a brawl broke out on the field and he piled on?

“As it turned out, I didn’t have any problems with Ron at all. I guess the prison experience must have helped him rather than hurt.”

LeFlore was put on a fast-track to the big leagues.

He started ‘74 in Class A, then after batting .331 with 45 steals in 102 games, Ronnie was promoted to Triple-A Evansville. His stay at Evansville lasted all of nine games before an injury to Mickey Stanley hastened his call-up to Detroit.

For someone with no formal outfield training, commanding the vast space that was CF in Tiger Stadium was no easy feat for LeFlore. He never did become a good outfielder, though he had a decent arm. His routes were less than efficient, despite working with Al Kaline every spring.

Billy was fired as Tigers manager late in the ‘73 season, but he watched LeFlore’s big league career blossom as manager of the Rangers, Yankees and A’s—usually from the opposing dugout.

When LeFlore arrived in Detroit, his speed turned on the crowds. He stole 23 bases in 59 games, albeit with a less-than-stellar .624 OPS. Seeing a fleet-footed ballplayer in a Tigers uniform was new for the Tiger Stadium patrons.

Even if that had been it for LeFlore’s big league career, he would have been one of baseball’s most fascinating stories. As it was, he played through the 1982 season, though his rapid decline after 1980 lent more credence to the whispers that Ronnie was more like 36 or 37 years old at the time.

LeFlore’s sometimes shady behavior and shadier associates clashed with new Tigers manager Sparky Anderson, leading to his trade to the Expos after the ‘79 season. He stole 97 bases in Montreal in 1980, then signed a free agent contract with the White Sox, where his decline occurred. His two years in Chicago were dotted with strange incidents, including falling asleep in the dugout during a game.

LeFlore’s post-baseball career included stints as an airline baggage handler and an aborted attempt to become an umpire.

Infamously, LeFlore was arrested immediately after closing ceremonies at Tiger Stadium on September 27, 1999 for being a deadbeat dad, officially bookending his baseball career with troubles with the law.

He lost a leg (ironically) in 2011 due to complications caused by arterial vascular disease.

In 2016, LeFlore waxed reflective on his life and baseball career.

“I really needed guidance and I didn’t get that. How come I couldn’t have gotten that guidance when I first came up? But I just didn’t have the guidance that I should have had. I had no support from anybody. I don’t know if they were afraid, because I was an ex-inmate, but nobody ever went out of their way to really help me. And I needed somebody. I really did. I really needed some help and some guidance, considering where I came from. And I didn’t get it.”

Then, a pensive thought—one for us all.

“Just think if I had played baseball as a kid instead of running the streets. Just think if I had improved my baseball skills instead of going to prison. How good could I have been?”

Good question.

But Ronnie LeFlore had his shot, despite how long it was. He turned on the baseball fans in Detroit for a few years with his speed, his sneaky power and his 30-game hitting streak in 1976 (leading to his only All-Star appearance). History has treated him well in Detroit, despite his flaws.

How has it been 50 years?